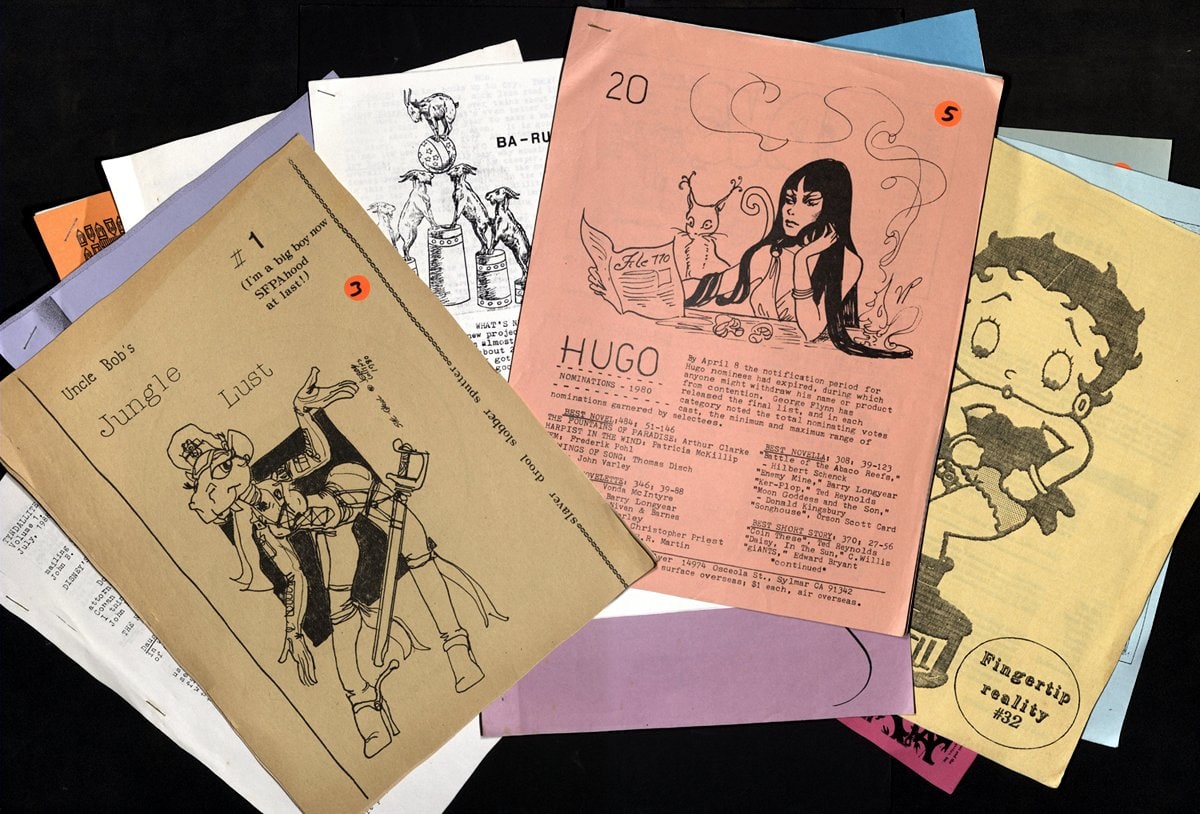

If you’re not familiar with the term fanzine, it’s short for “fan magazine,” and typically refers to the kind of fan-made, photocopied magazines that popped up in decades past.

While fanzines are obviously not professionally published, to consider their influence to be as basic as the medium would be missing the point. To help you understand a little more about this pop culture phenomenon, here’s a little ‘zine primer — along with more than 20 examples.

What is a fanzine?

Merriam-Webster defines fanzine as “a magazine that is written by and for people who are fans of a particular person, group, etc.” — but that doesn’t remotely capture the essence of the fanzine movement.

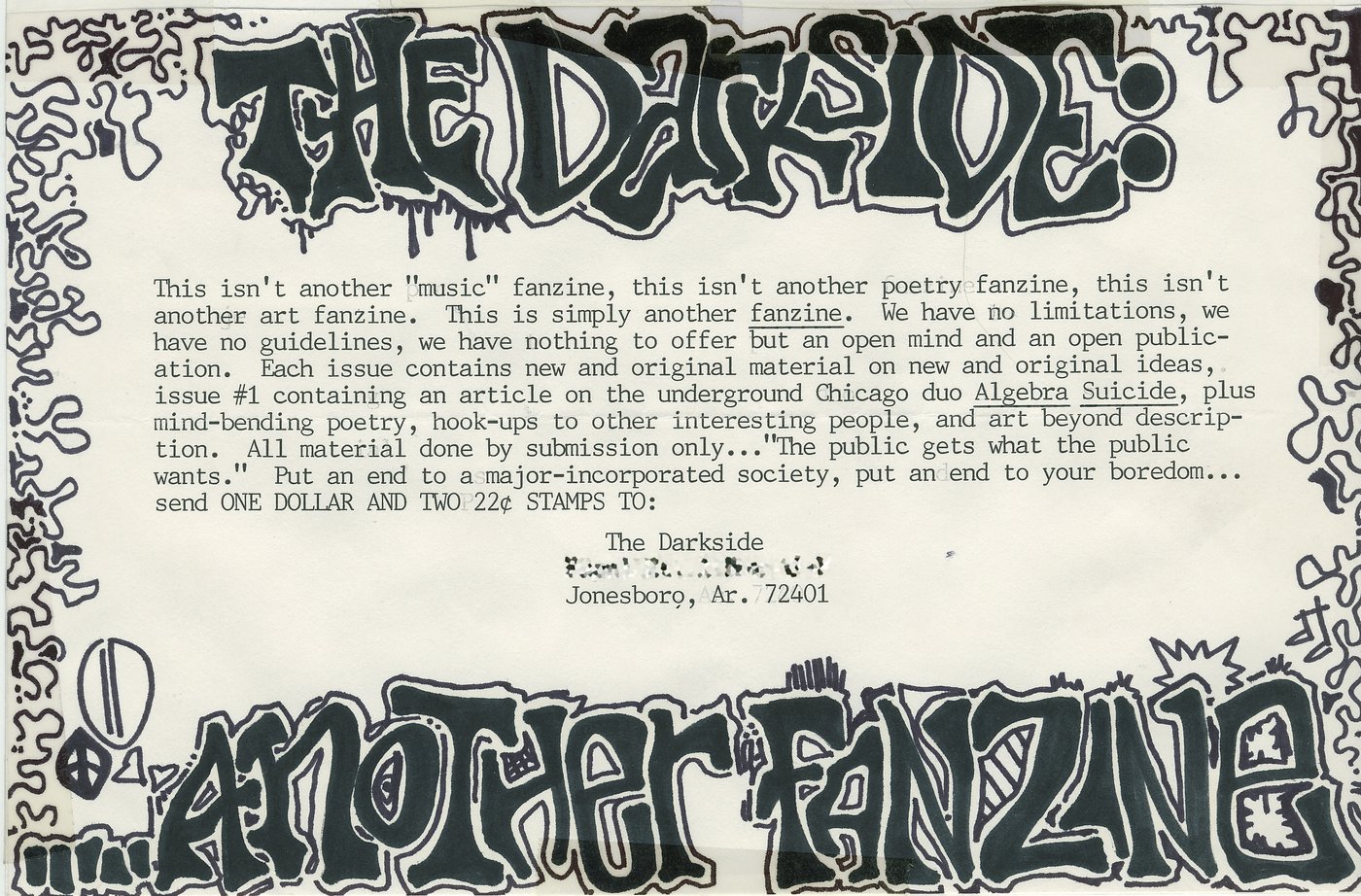

An article from 1984 explained it much better: “One of the most recent phenomena of the pop culture melting pot are fanzines. A fanzine is something akin to an underground magazine, and there are virtually thousands of them springing up all over the country.

“Fanzines cover a wide spectrum of ideas; the articles, interviews and band reviews, however, are not written in a style found in conventional media. The majority of fanzines are put together in a chaotic fashion; poetry, art dabblings, discussions of social and economic repression and articles about non-mainstream bands abound.”

If you had to explain fanzines to a teen using today’s parlance, you might say it’s kind of like creating a public blog to share the best fan art, fanfic, comics, commentary and clips with all of your like-minded friends from the various social media sites. (Ironically, there’s even a tumblr about fanzines.)

Fanzines by the thousand

Over the years, thousands of these DIY publications have produced by hobbyists and other obsessive types. The vast majority were labors of love — created out of a passion for the subject matter — and not expected to make a profit. (The typical goal was just to cover the costs of photocopying and postage.) Readers got to experience the joy of a stapled bundle of black print on plain paper showing up in the mailbox at random intervals.

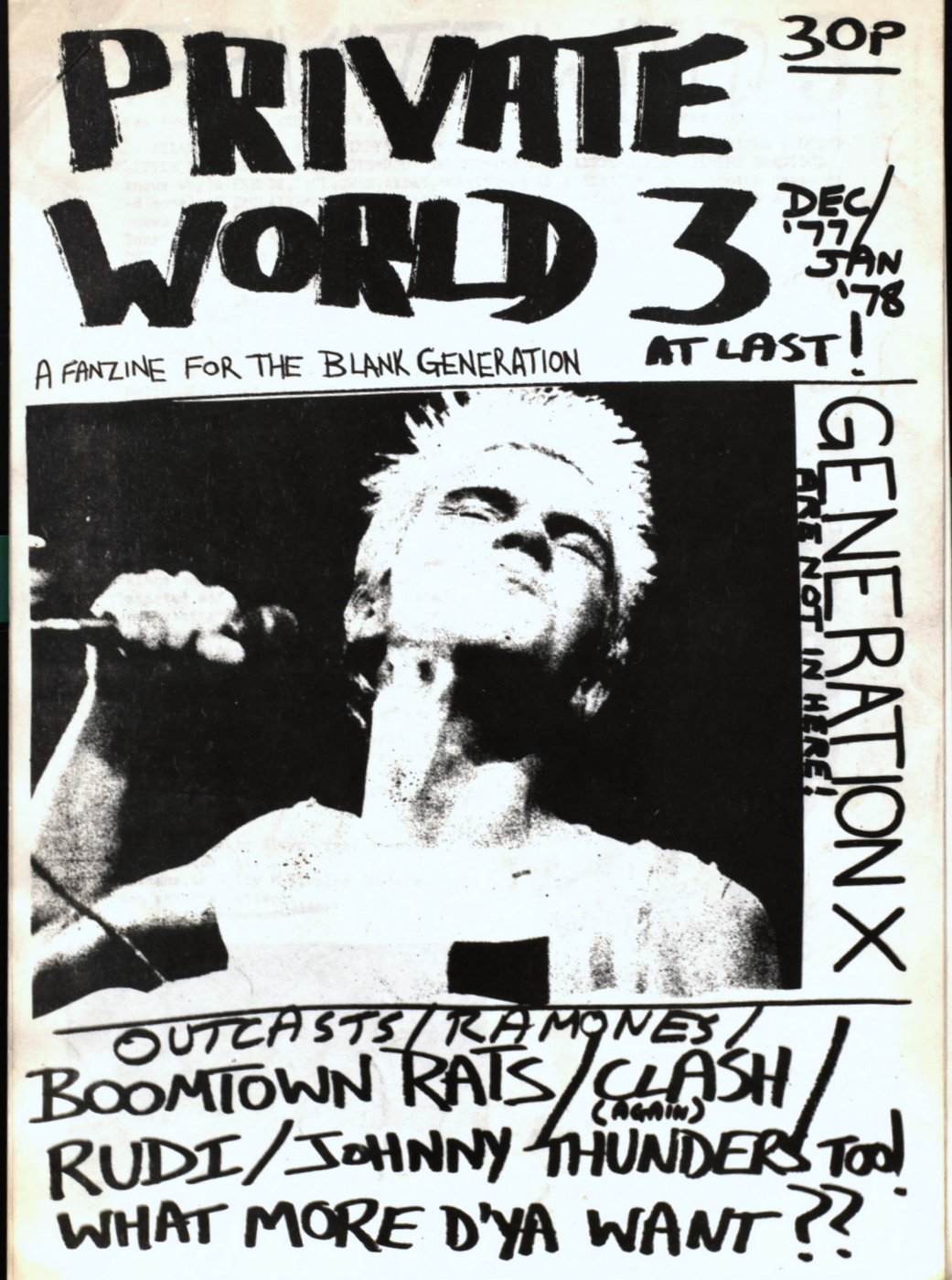

The subject matter varied widely, though the self-published works started by science fiction fans back in the 1930s are considered to be the first ‘zines.

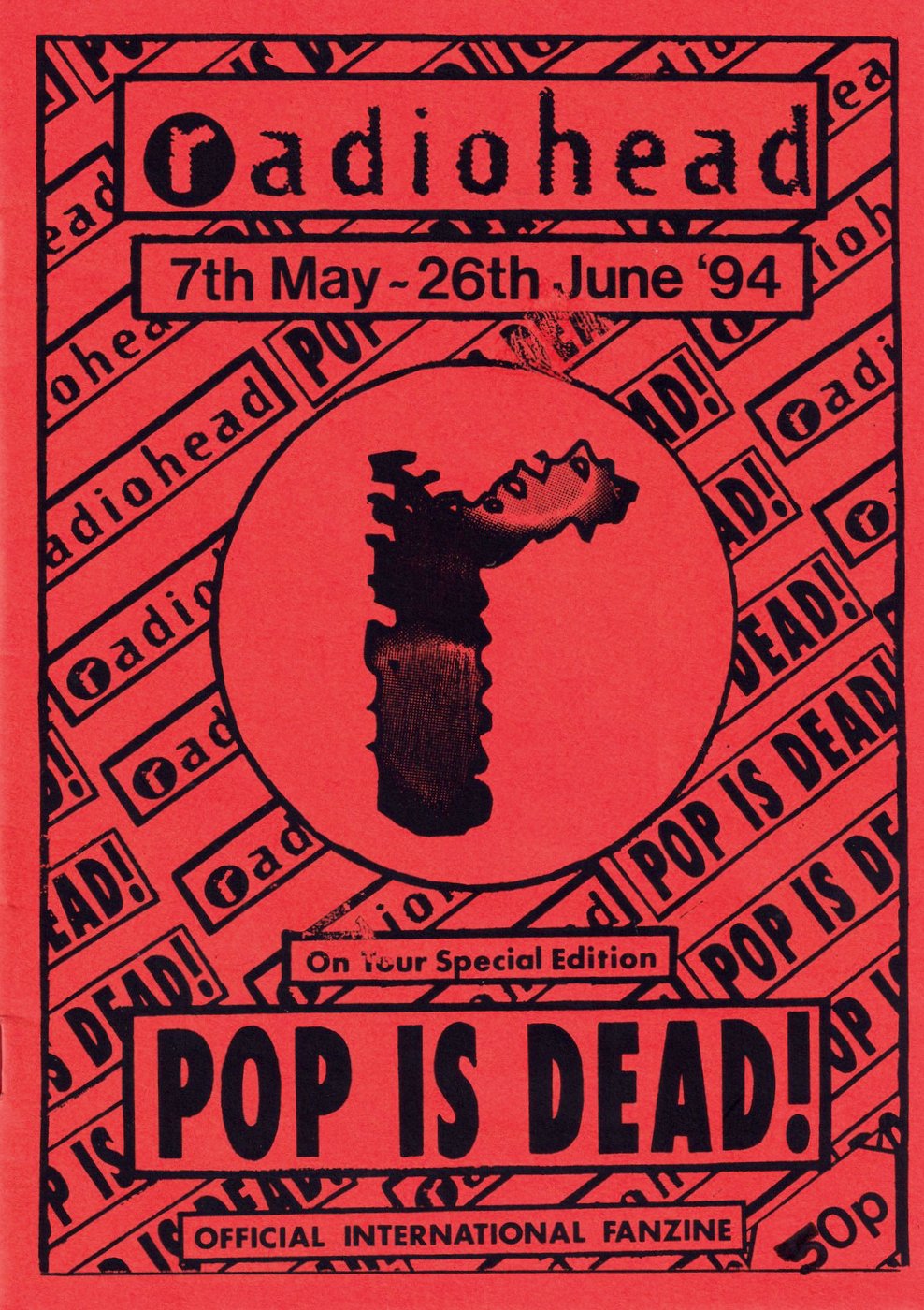

The concept slowly worked its way into the music world during the late 1970s and early 1980s — but there were absolutely no limits on the types of topics covered. In fact, “no limits” pretty well describes the overall fanzine philosophy pretty well — just as “no budget” sums up the resources usually used to create such works.

While rarely intended for the mainstream, fanzines are now considered an important part of world culture, and several pillars of academia — including Duke, Harvard, University of Arizona, University of Maryland and the University of Iowa — have fanzine collections.

The University of Iowa, working to digitize about 10,000 science fiction ‘zines, explains the fascination as so: “Fanzines are important cultural artifacts that document the development and continuing life of particular social communities — in this case, fans of specific genre topics (i.e. science fiction).

“Fanzines were originally devoted to chronicling people’s interest in literary science fiction, but over the course of the 20th (and into the 21st) century, they have been adopted as vehicles of personal and cultural expression by a number of new fan communities.”

A brief history of fanzines

“Psychologist Frederic Wertham, one of the first scholars to study fanzines, recognizes the impulse behind their creation and use: ‘Their claim to attention, certainly not a small one, lies in the fact that they belong to the American cultural environment, that they exist as genuine human voices outside of all mass manipulation.’ (1973)” noted a research paper by archivist Jeanne Swadosh.

She further explains, “Feeling alienated from mediated reality and the geographic communities in which they lived, worked, and studied, these individuals began producing their own low-circulation print publications for distribution amongst like-minded others. Sometimes centered around a particular topic, but just as likely not, these publications were created to communicate highly personal thoughts, opinions and questions to a diffused, international audience.

“Using non-traditional communication networks and the US Postal Service, fanzine and zine publishers established a framework for intimate, meaningful, open discourse outside and in opposition (sometimes unconsciously, sometimes not) to corporate control.”

MORE: Why we still love the music we listened to while growing up

People are still producing fanzines, of course, but there aren’t nearly as many as there were in years past. Their decline is largely due to the advent of the internet — which has made content creation simpler, distribution fast and cheap, while also allowing for easy interaction between readers and online publishers.

The attraction of fanzines

“The more raw and honest, the better. It’s a world where the weird, absurd and unique is appreciated,” explain Esther Watson and Mark Todd in their book Whatcha Mean, What’s a Zine?. “It’s for getting thoughts and ideas down on paper and into others’ hands.”

But beyond servicing a readership, ‘zines opened doors by helping other people realize, “Hey — I can do this, too!” In fact, Myria was co-founded by a former ‘zine editor — and she’s not the only one who launched a career that way.

“Walking into a record store and scanning the bottom shelves of the diminutive magazine rack, I picked up my first ‘zine. It was handmade using tape, typewriters, pens and a photocopier,” writes Eric Nakamura, who went on to co-create Giant Robot.

And then he describes the magic: “It had the energy of punk rock, but it was captured in print — all for $2.”

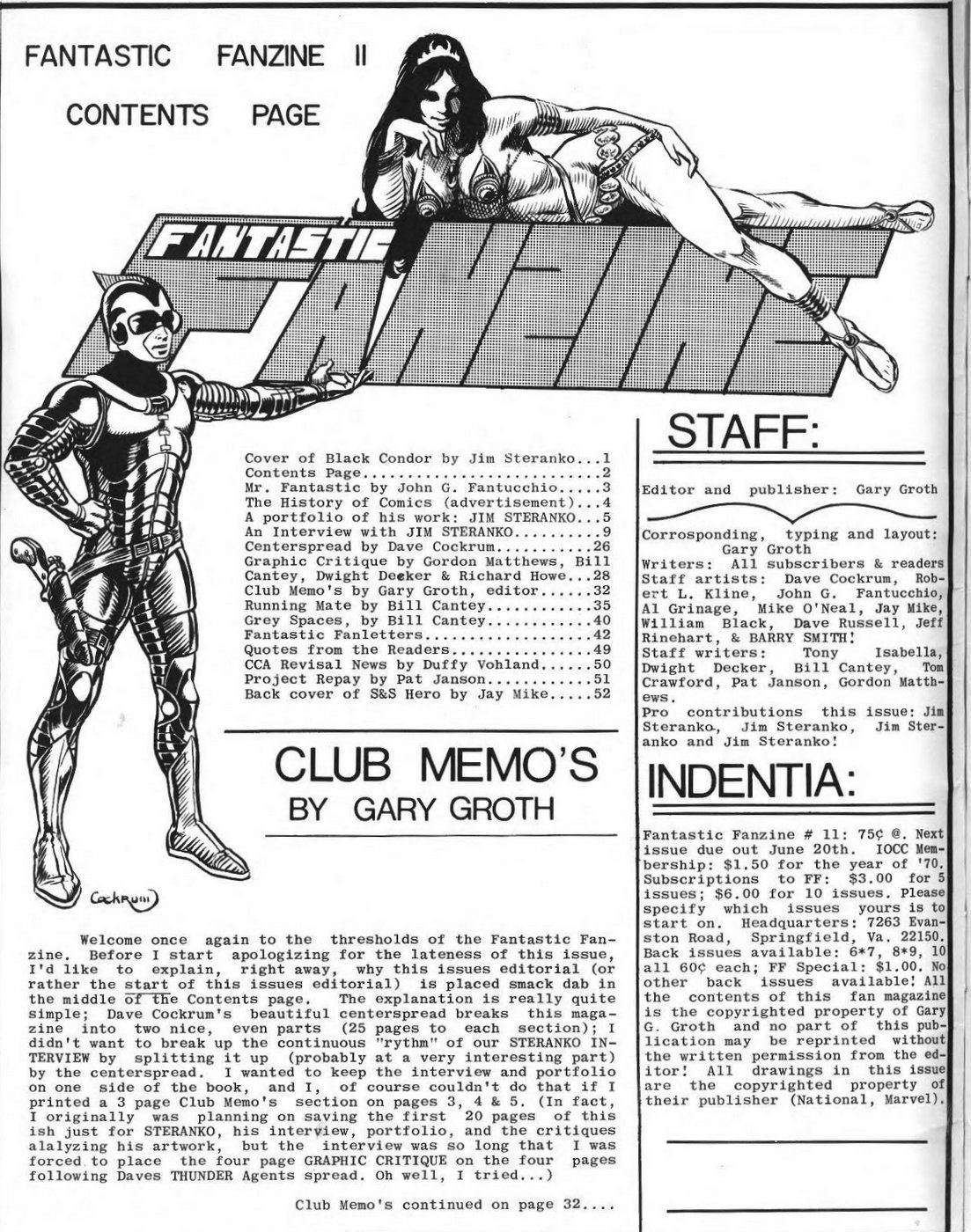

Fanzines from the 1970s

Vintage Fantastic Fanzine (1970)

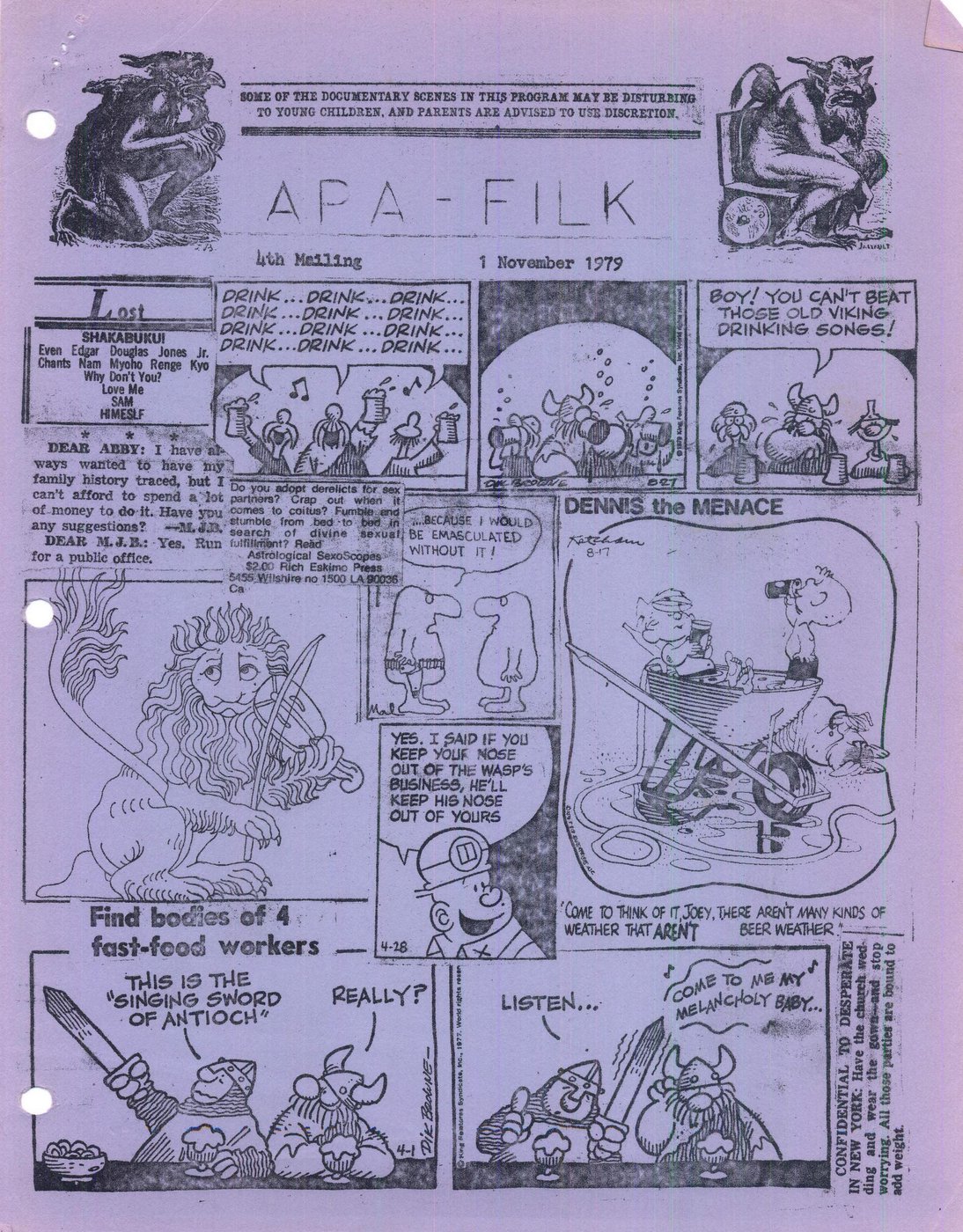

APA-FILK fanzine (1979)

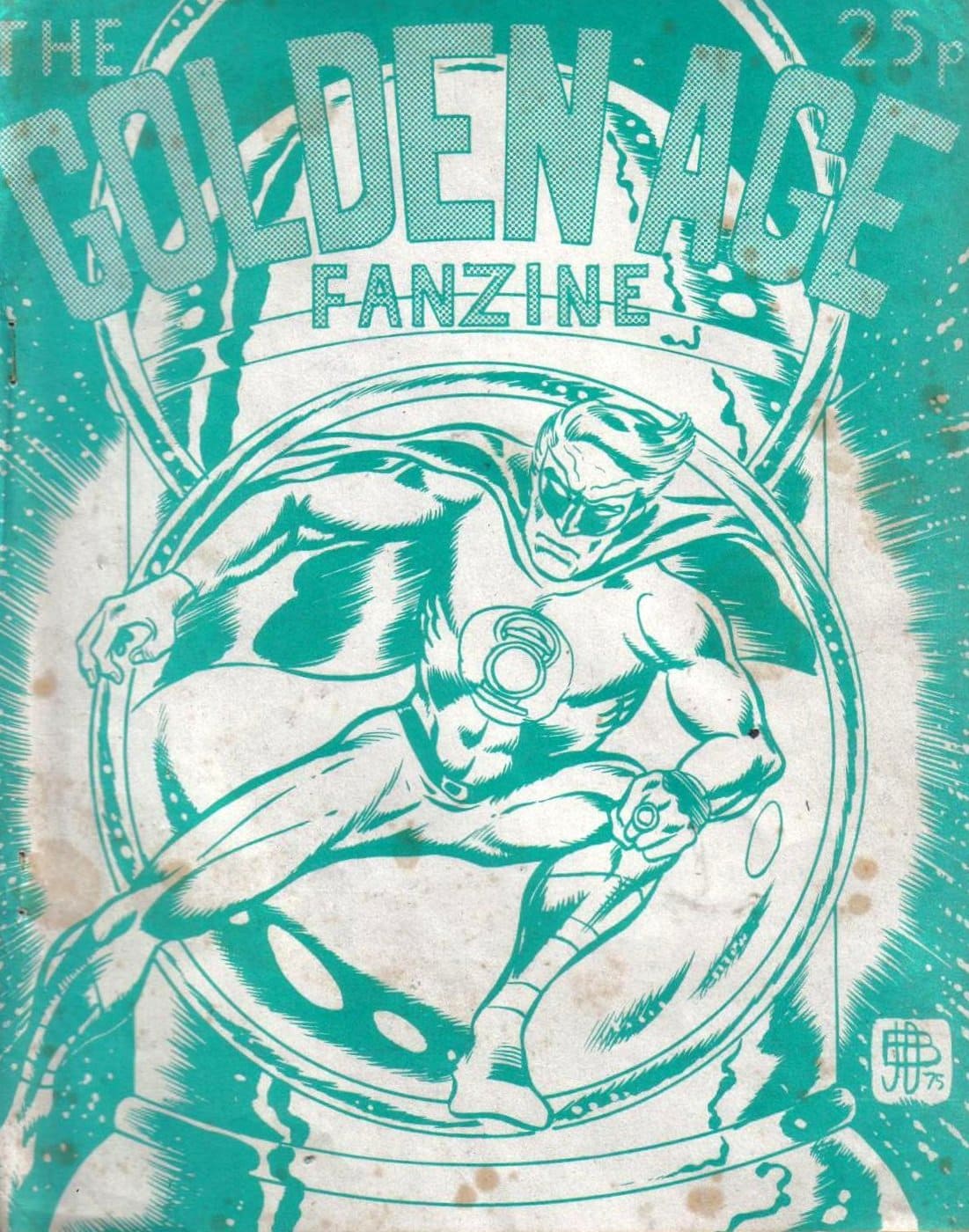

The Golden Age fanzine (1976)

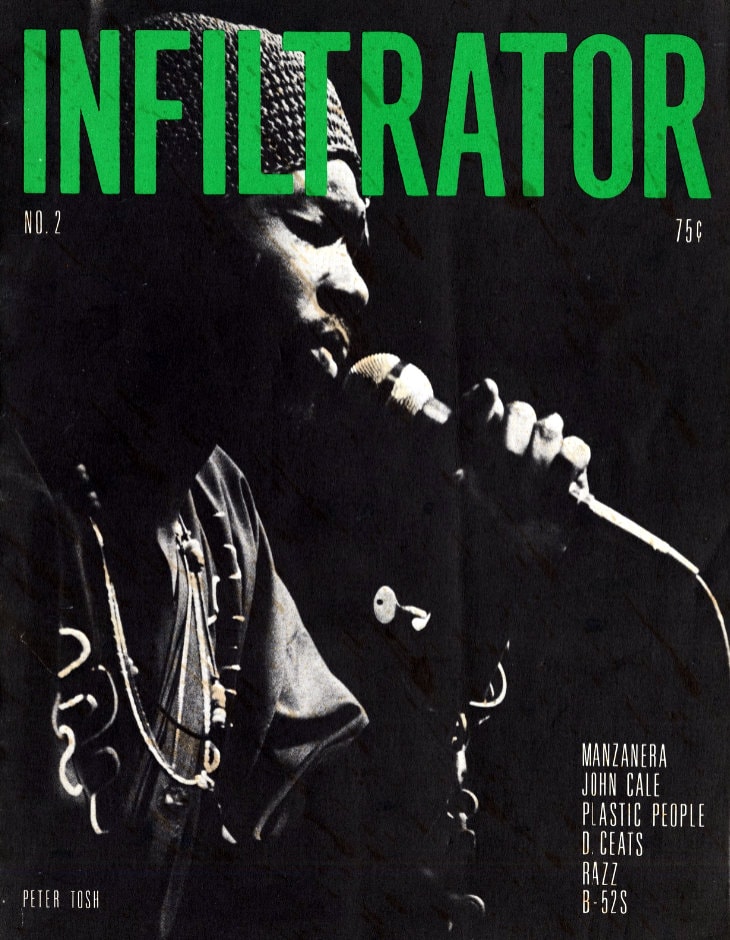

Infiltrator music fanzine (1979)

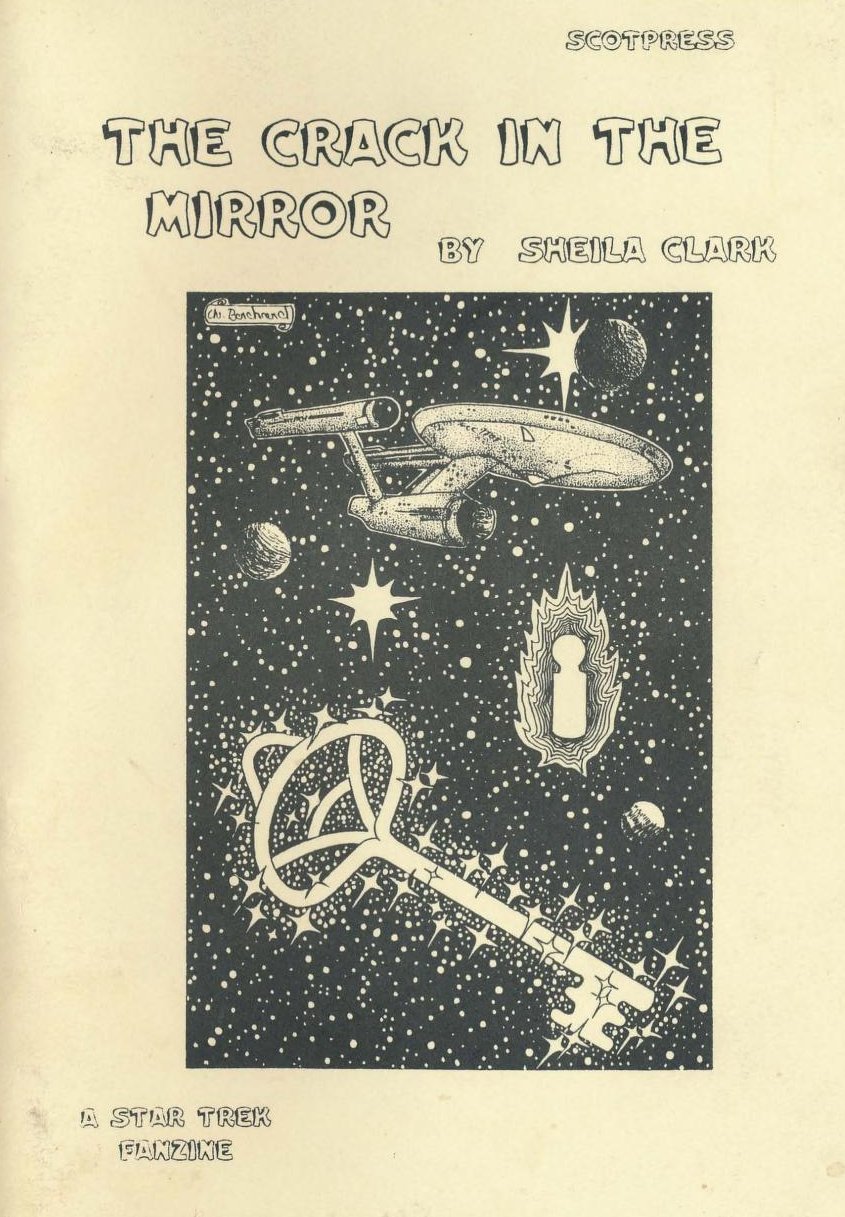

Star Trek Crack in the Mirror fanzine

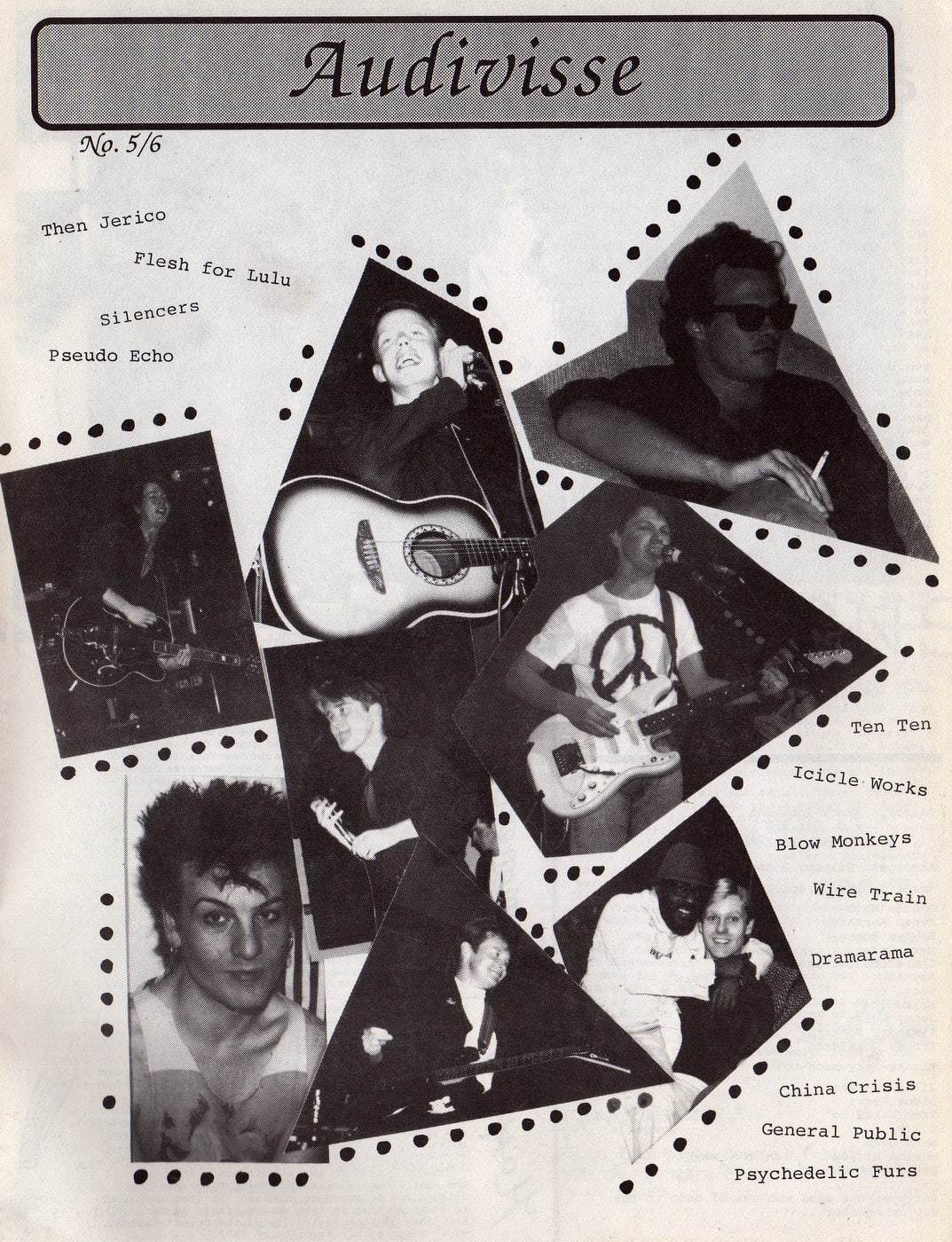

1980s fanzines: Chaotic dabblings from the eighties

Fanzines emphasize the negative side of everything, but still manage to be witty and thought-provoking.

From an article by Jim Reichenberger – Oshkosh Advance Titan (UW Oshkosh) March 22, 1984

One of the most recent phenomena of the pop culture melting pot are fanzines. A fanzine is something akin to an underground magazine, and there are virtually thousands of them springing up all over the country.

Fanzines cover a wide spectrum of ideas; the articles, interviews and band reviews, however, are not written in a style found in conventional media.

The majority of fanzines are put together in a chaotic fashion; poetry, art dabblings, discussions of social and economic repression and articles about non-mainstream bands abound.

Madison is the center of six fanzines. One of them, “Catholic Guilt,” takes editorial stands against the city’s bike monitors, who the fanzine’s editors feel are sexist because they, reportedly, “discuss women’s asses while on duty.” The fanzine also takes stands against the no skateboard ordinance on Madison’s sidewalks.

“Catholic Guilt,” like many fanzines, has its own unique brand of humor. In a recent issue, there is a page spoofing the television game show “Let’s Make A Deal,” depicting Ronald Reagan as Monty Hall and Nancy Reagan as Carol Merrill.

In “Catholic Guilt’s” version of “Let’s Make A Deal,” Door Number One is a vacation in Beirut, where you’ll be greeted by two hundred-plus dead Marines, Door Number Two is a vacation to Europe, where you’ll be greeted by Russian counter missiles in the European theater of war and Door Number Three is a package vacation to Central America, including a military safari to hunt Salvadoran peasants and a luxury cruise on Navy ships off Honduras. Fittingly, “Catholic Guilt” contains much about religious taboos and hypocrisy.

“Reagan Death,” another fanzine from Madison, is not recommended for those who are easily offended. In a recent issue, for instance, there is a picture of Christ hanging on the cross, saying, “What a waste of spring break.”

Northeastern Wisconsin is home for two fanzines, “Sick Teen” from Green Bay and “No Nations” from the Fox River Valley. “Sick Teen’s” print is so minuscule that perseverance is needed to get through it, although there are rewards for those who do.

“No Nations”‘ theme questions conformity, ignorance and patriotism. Recently, one of their blurbs was about Reagan using a top-secret time machine to visit Hitler on New Year’s Weekend 1940, where sources said they discussed foreign policy and election tactics. Real hilarious, huh?

“Maximum Rock & Roll” is put together in Berkeley, Calif., and contains material from across the states, as well as from around the world. “Maximum Rock & Roll” is primarily a forum for band promotion. The letters to the editor, however, are more politically oriented.

Fanzines, in general, convey the impression that people are groping for identity in the potluck mid-’80s. As a means of expression in this context, they are probably worthwhile.

Some other fanzines are Rockabilly Rag,” a rockabilly revivalist fanzine out of Madison, “Kickass Monthly,” a heavy metal fanzine, “Touch & Go,” “Ephemeral Youth,” “Forced Exposure” and “Sub/Pop,” whose table of contents reads, “Nursing Home Weirdness, Bootlegged Swedish Radio, Eastern Bloc Hardcore, Lust, Gunshots, Rhythm.”

Fanzines are necessarily low budget and published sporadically. They’re an avenue of communication for persons who seek an alternative to the Cosmopolitan norm.

Fanzines are overtly negative, but covertly positive in spirit and intent. They’re thought-provoking, humorous, and worth checking out. Don’t be debauched by polyester.