Have you or one of your family members ever fallen for a phone or online scam — and, looking back, can’t figure out why it was so easy to fall for such a con?

Researchers have found evidence that the incredible spread of email scams may be due to the con’s increased use of “information-rich” emails that alter our thought processes in a way that makes us easier to victimize.

When internet fraudsters impersonate a business to trick someone into giving out personal information — even if it’s just logging into an account — it’s called phishing.

Although people of all ages are vulnerable, Boomers and Silent Generation members are especially vulnerable. This is both due to many older people being less savvy to scams perpetrated through electronic means — phone calls, emails, texts and more — as well as the fact that the cons are skilled at targeting their specific concerns.

“Some common triggers that target Boomers include scams related to the IRS, healthcare, social security, credit cards, and consumer warranties,” says Mitek Systems, an identity verification provider that works with businesses.

Meanwhile, we in Generation X have our own vulnerabilities. Some common fraud tactics used to engage with Gen X include robocalls, SMS/texts, and emails. “Fraud victims within Gen X are more likely to be vulnerable to triggers such as financial information, interest rates, and parcel pickup,” Mitek notes. “Criminals frequently tap into these vulnerabilities to conduct scams and other criminal activity.”

Phishing: What it is, and examples of these scams

Bottom line: As a rule, do not reply to emails, phone calls, texts, direct messages, pop-up messages or other notifications that ask for your personal or financial information. Don’t click on links within them, either — even if the message seems to be from an organization you trust.

It isn’t. Legitimate businesses don’t ask you to send sensitive information through insecure channels. They want you to click the helpful link they have sent so you try to log in as if you’re on your usual banking site or another website. When you do, they steal your user name and password and can use it on the actual banking site to take your money.

Examples of phishing messages

You open an email or text, and see a message like this:

“We suspect an unauthorized transaction on your account. To ensure that your account is not compromised, please click the link below and confirm your identity.”

“During our regular verification of accounts, we couldn’t verify your information. Please click here to update and verify your information.”

“Our records indicate that your account was overcharged. You must call us within 7 days to receive your refund.”

The senders are phishing for your information so they can use it to commit fraud.

PS: If you get a call — or repeated calls — about a home or car warranty expiring, consider that a red flag that you have been targeted.

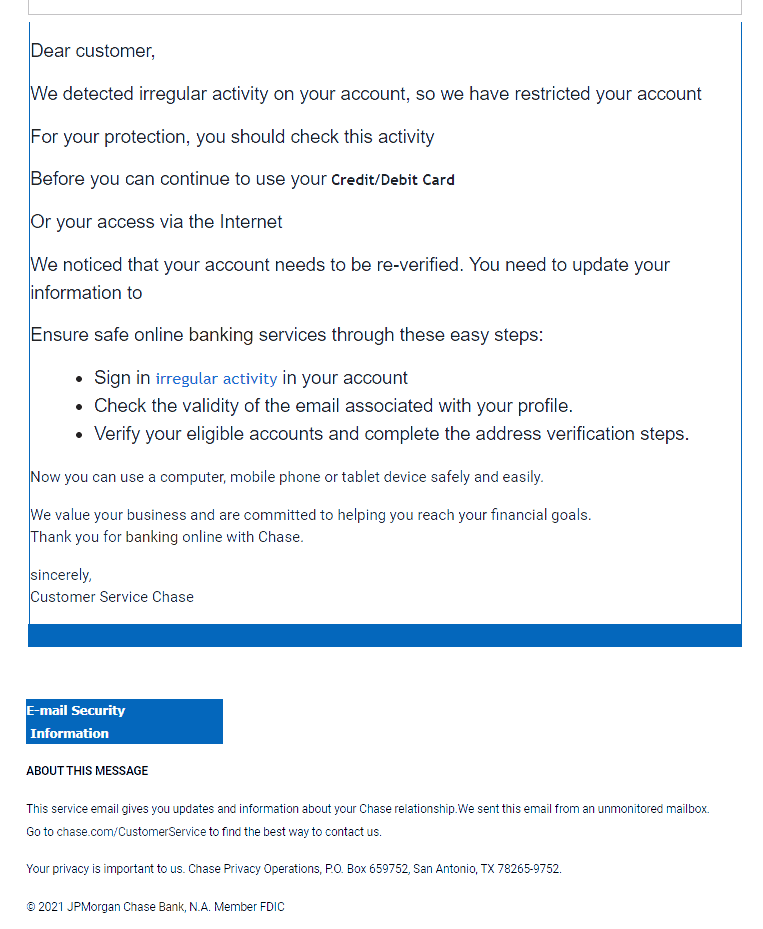

A real phishing email from 2021

How to deal with phishing scams

Delete email and text messages that ask you to confirm or provide personal information (credit card and bank account numbers, Social Security numbers, user names, passwords, etc.). Legitimate companies don’t ask for this information via email or text.

The messages may appear to be from organizations you do business with – banks, for example. They might threaten to close your account or take other action if you don’t respond.

Don’t reply, and don’t click on links or call phone numbers provided in the message, either. These messages can direct you to spoof sites – sites that look real but whose purpose is to steal your information so a scammer can run up bills or commit crimes in your name.

Area codes can mislead, too. Some scammers ask you to call a phone number to update your account or access a “refund.” But a local area code is no longer any guarantee that the caller is local (even if it would make a difference).

If you’re concerned about your account or need to reach an organization you do business with, call the number on your financial statements or on the back of your credit card, or manually type the bank or site name in your browser, verify it has connected correctly to the domain, and then check your account for any alerts or messages.

Action steps

You can take steps to avoid a phishing attack:

Use trusted security software and set it to update automatically. Get some tips here: How & why you should always practice safe computing.

Don’t email, text or use messages/DMs to send any passwords, access codes, personal or financial information. Email, text and messaging are not secure methods of transmitting personal information.

Only provide personal or financial information through an organization’s website if you typed in the web address yourself and you see signals that the site is secure, like a URL that begins https (the “s” stands for secure). Unfortunately, no indicator is foolproof; some phishers have forged security icons.

Review your credit card and bank account statements as soon as you receive them to check for unauthorized charges. If your statement is late by more than a couple of days, call to confirm your billing address and account balances.

Set up smartphone alerts whenever a purchase is made on your credit card. Almost all banks offer this service free of charge to help fight fraud. Check their site or contact their customer service to set them up.

Be very cautious about opening attachments and downloading files from emails, regardless of who sent them. These files (even if they look harmless) can contain viruses or other malware that can weaken your computer’s security.

Report phishing emails

Forward phishing emails to [email protected] — as well as to the company, bank, or organization impersonated in the email. Do not hit reply on the email — actually use a well-known search engine to visit the bank’s official site, and send an email from there.

You also may report phishing email to the Anti-Phishing Working Group, a group of ISPs, security vendors, financial institutions and law enforcement agencies, that uses these reports to fight phishing.

How cons mess with your mind to get what they want

Arun Vishwanath, professor of communication at the University at Buffalo, and co-author of the study, “Examining the impact of presence on individual phishing victimization,” says “information-rich” emails include graphics, logos and other brand markers that communicate authenticity.

“In addition,” he says, “the text is carefully framed to sound personal, arrest attention and invoke fear. It often will include a deadline for response for which the recipient must use a link to a spoof ‘response’ website.

“Such sites, set up by the phisher, can install spyware that data mines the victim’s computer for usernames, passwords, address books and credit card information.

“We found that these information-rich lures are successful because they are able to provoke in the victim a feeling of social presence, which is the sense that they are corresponding with a real person,” Vishwanath says.

“‘Presence’ makes a message feel more personal, reduces distrust and also provokes heuristic processing, marked by less care in evaluating and responding to it,” he says. “In these circumstances, we found that if the message asks for personal information, people are more likely to hand it over, often very quickly.

“In this study,” he says, “such an information-rich phishing message triggered a victimization rate of 68 percent among participants.

“These are significant findings that indicate the importance of developing anti-phishing interventions that educate individuals about the threat posed by richness and presence cues in emails,” he explains.

Urgency and fear common triggers

The study involved 125 undergraduate university students — a group often targeted by phishers — who were sent an experimental phishing email from a Gmail account prepared for use in the study. The message used a reply-to address and sender’s address, both of which included the name of the university.

The email was framed to emphasize urgency and invoke fear. It said there was an error in the recipients’ student email account settings that required them to use an enclosed link to access their account settings and resolve the problem. They had to do so within a short time period, they were told, otherwise they would no longer have access to the account.

In a real phishing expedition, the enclosed link would take them to an outside account/phishing site that would collect the respondent’s personal information.

Vishwanath says 49 participants replied to the phishing request immediately, and another 36 replied after a reminder. The respondents then completed a five-point scale that measured their use of systemic (critical thinking) and heuristic information processing in deciding what to do with the email. When a few other variables were factored in, the phishing attack had an overall success rate of 68 percent.

“With email becoming the dominant way of communicating worldwide,” Vishwanath says, “the phishing trend is expected to increase as technology becomes more advanced and phishers find new ways to appeal to their victims.

“While these criminals may not be easily stopped, understanding what makes us more susceptible to these attacks is a vital advancement in protecting Internet users worldwide.”