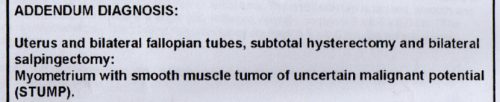

When you have surgery to remove a tumor — even if it’s a totally common uterine fibroid tumor — the number one thing you’re waiting to hear is whether it was cancerous or not.

But what many people don’t realize is that even in this day of high-tech pathology labs, it’s not always easy to classify tissue as being distinctly malignant or benign. In fact, in some rare cases, doctors really can’t determine for sure whether or not cancer is present.

Cancer isn’t always obvious

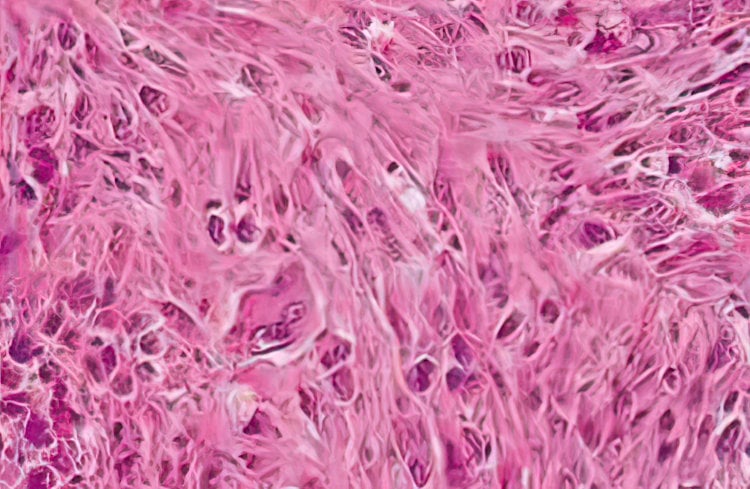

Whenever something is surgically removed from someone, that tissue isn’t just immediately incinerated. Instead, it finds its way to a pathologist, who will examine it with the naked eye as well as under a microscope, often looking to detect any cancer. (Surgical pathology is defined by The Johns Hopkins Hospital as “the study of tissues removed from living patients during surgery to help diagnose a disease and determine a treatment plan.”)

But here’s where it gets complicated: Some unusual tumors show signs of being cancerous as well as indications of being benign.

This is not normal, based on what doctors and scientists know about cancer so far. The vast majority of the time, it’s pretty clearly one or the other.

You could think of it kind of like a light switch: it’s on or it’s off. But in the case of certain “tumors of uncertain malignant potential,” it’s more like the light switch might be on or could be off… but there’s no way to tell because the lightbulb is missing.

When that happens, it’s impossible to state definitively whether someone is at risk of cancer spreading through her body, or if she can be safely be given a clean bill of health.

Tumors of uncertain malignant potential

Most commonly (and that’s a relative term), this kind of mysterious diagnosis is related to a uterine tumor, and is called a “smooth muscle tumor of uncertain [unknown] malignant potential” — shortened to the ugly acronym STUMP.

This I know not just from reading scores of research papers or talking to doctors, but because I got the frustrating and worrisome diagnosis myself.

SEE MORE: The hysterectomy story: An adventure in two parts

Rare, but not unknown: The history of STUMPs

My first response, of course, was to scour the web for information about this rare creature.

Pathology research published in 2011 by the Indian Journal of Pathology and Microbiology noted, “Uterine smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP) are uncommon tumors. They are unclassifiable by current criteria as unequivocally benign or malignant.”

In 2012, a study in the Journal of Research in Medical Sciences stated, “One of the most controversial concepts on the subject of uterine smooth muscle tumors is smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP), a term first used by Kempson in 1973. These are a group of heterogeneous and uncommon uterine smooth muscle tumors which fulfill some but not all the diagnostic criteria for leiomyosarcoma.”

“Histological diagnosis is challenging and usually problematic,” said a case report from 2012 published in the Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. The authors added, “Natural history of the disease, as well as the malignant potential, remains uncertain. They are usually clinically benign but, in some cases, recurrence can occur many years following hysterectomy.”

Rare tumors aren’t unique to the uterus, however. The same kind of ambiguous tissue can appear elsewhere in the body.

For example, there’s a similar STUMP diagnosis in men for “stromal tumors of uncertain malignant potential” found in the prostate, while “melanocytic tumors of uncertain malignant potential” (MELTUMP) are essentially skin moles that are puzzling.

“Thyroid tumors of uncertain malignant potential” have been dubbed TT-UMP, while “glomus tumors of uncertain malignant potential” earned the nearly unpronounceable nickname GTUMP.

Very little to go on

Typically, physicians review medical research, case studies and existing pathology reports to review and learn about issues they see in practice. But because tumors of this type are so unusual, there is very little information about them in the medical literature, leaving most doctors at a loss.

In the words of the authors of a 2009 analysis published in The American Journal of Surgical Pathology, “STUMPs represent a heterogeneous group of rare tumors that have been the subject of only a few published studies, some of which lack detailed clinicopathologic details and/or follow-up data.”

So deep is the void that Dr Anais Malpica, Department of Pathology, Division of Pathology-Lab Medicine Division at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Texas, made it a topic of discussion at a major pathology meeting in August 2012. The title of her presentation? “Uterine Smooth Muscle Tumors that Nobody Wants to Talk About.”

Of benign-appearing smooth muscle tumors in the uterus and other anatomical sites, she writes, “They can represent a true paradox and a management challenge.”

Additional research on STUMP

Several more recent studies have been published, although none offer conclusive answers. Here’s a sampling:

Recurrent Uterine Smooth-Muscle Tumors of Uncertain Malignant Potential (STUMP): State of The Art (2020)

Uterine STUMP represents a therapeutic dilemma, and further observational data would be required to reach a consensus concerning management balancing the indolent clinical course against the malignant, even lethal, potential…

A future perspective may be to identify the molecular basis of STUMP using molecular biology techniques. The identification of key genes directly involved in the carcinogenesis of STUMP may suggest novel opportunities in the management of the disease and provide further information in understanding the process of carcinogenesis.

At the first operation, 21 cases underwent myomectomy and 10 cases underwent hysterectomy. The patients in myomectomy group were younger than those in hysterectomy group.

In the follow-up period, two cases experienced a relapse in the form of STUMP within 36 months. One case died of cardiovascular accident while the other cases were alive. Six of 21 women in myomectomy group desired pregnancy and two healthy live births were recorded.

Sonographic features of smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential may vary and a pathognomonic description has not been recognized. However, the identification of single or multiple lesions with specific ultrasound features should raise the suspicion of tumors of uncertain malignant potential.

Rare Case of Smooth Muscle Tumor of Uncertain Malignant Potential – Clinical Case (2021)

Due to the rarity of these tumors, the scientific literature needs to be constantly updated in order to help physicians to correctly identify and treat this pathology. It is highly recommended to identify tumors with a high malignancy potential, so that the follow up will be sufficient to discover and treat recurrences before they become life-threatening.

Help for the layperson

While medical professionals have very little data with which to work, there’s practically nothing out there for patients who have been given a STUMP diagnosis.

Sifting through the medical research can be a daunting task — not to mention that not every outcome described is hopeful.

The aforementioned 2009 analysis stated that STUMPS “are usually clinically benign but should be considered tumors of low malignant potential because they can occasionally recur, in some cases, years after hysterectomy,” and added, “Patients diagnosed with STUMPs should receive long-term surveillance.”

That’s why almost all patients with STUMPS are asked to see a gynecologic oncologist at regular intervals — every six months or so seems typical.

Follow-up surgery may also be advised to remove at-risk tissue. For example, if you had a fibroid removed and it ended up being a STUMP, a hysterectomy might be recommended. In my case, I had a sub-total hysterectomy, which left the cervix behind.

Three months later, I was back in the operating room for an even more complex surgery to remove all traces of my uterus.

The checkups and surgeries are all part of the “be on the safe side” medical plan, which is the best anyone can do for now.

“In these tumors, it is simply impossible with current tools to predict the behavior with certainty, and this makes their management difficult. What makes the management more complicated is the difficulty in counseling patients with regards to the likely clinical behavior,” reads another 2012 report published in the Journal of Research in Medical Sciences.

“However,” they say, “data from literature suggest a low risk of recurrence and a generally good clinical outcome.”

As for me, it’s been seven years since my STUMP was removed (along with my uterus) and there has been no recurrence or any other related issues.

Real-life STUMP pathology reports (second and third opinions)

Some basic definitions and links have been added, while names of doctors and labs have been removed.

Surgical pathology report 1

This is a challenging case.

The sections show a myometrial smooth muscle neoplasm with no nuclear atypia and zero mitotic figures per ten high-power fields (50 high power fields counted).

The most concerning feature, however, is the presence of abundant necrosis with abrupt transitions between viable and necrotic cells, ghost tumor cell outlines:, and perivascular spacing. Other areas have an appearance suggesting an infarct [Tissue death because of an interrupted blood supply], however, with a hyalinized [glassy or transparent appearance] zone surrounding the necrosis.

Given the presence of ambiguous necrosis, I would regard this tumor as a smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP), and would recommend close clinical follow-up.

Due to the difficult nature of this case, I have shared it with my colleague [doctor name], who concurs with the above interpretation.

Surgical pathology report 2

Sections of uterus have a benign endometrium without evidence of glandular hyperplasia or neoplasia. Sections of the myometrial mass have extensive hemorrhagic necrosis. Collections of bland spindled nuclei focally arrange themselves in Verocay body-like formations. There is no associated nuclear pleomorphism. No mitotic figures are identified.

The interface with the subjacent myometrium is smooth without areas of infiltration. The differential diagnosis in this case would include an infarcted leiomyoma as well as an infarcted smooth muscle tumor of low malignant potential.

A smooth muscle tumor of low malignant potential is favored given the current subclassification of so-called uterine stump (smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential). The smooth muscle tumor of low malignant potential is characterized by none to mild atypic, loss than ten mitoses [cell divisions] per ten high-power fields [magnification level under a microscope], and tumor cell necrosis [cell death]. As noted above, tumor cell necrosis is prominent in this case.

Of such cases in the literature four of 15 recurred. Material from this case had been previously referred to [major pathology lab]. Their favored diagnosis was one of a smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential.

A pertinent reference in this regard would include Phillip, PC IP et al. Uterine smooth muscle tumors other than the ordinary leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas: a review of selected variants with emphasis on recent advances and unusual morphology that may cause concern for malignancy. (Adv Anat Pathol. 2010 Mar;17(2):91-112)